For as long as I can remember, I have bought food from the same grocery store. It’s only in these last few visits that I have begun to notice a problem. Rot. Black specks of mold dot the cheeses, the lettuce is already wilted and powdery mildew grows in the blueberry containers. Even the new products have problems of their own, as they are packed with ingredients with names most can’t pronounce and are cheaper but worse for my health. When did fresh food become a luxury?

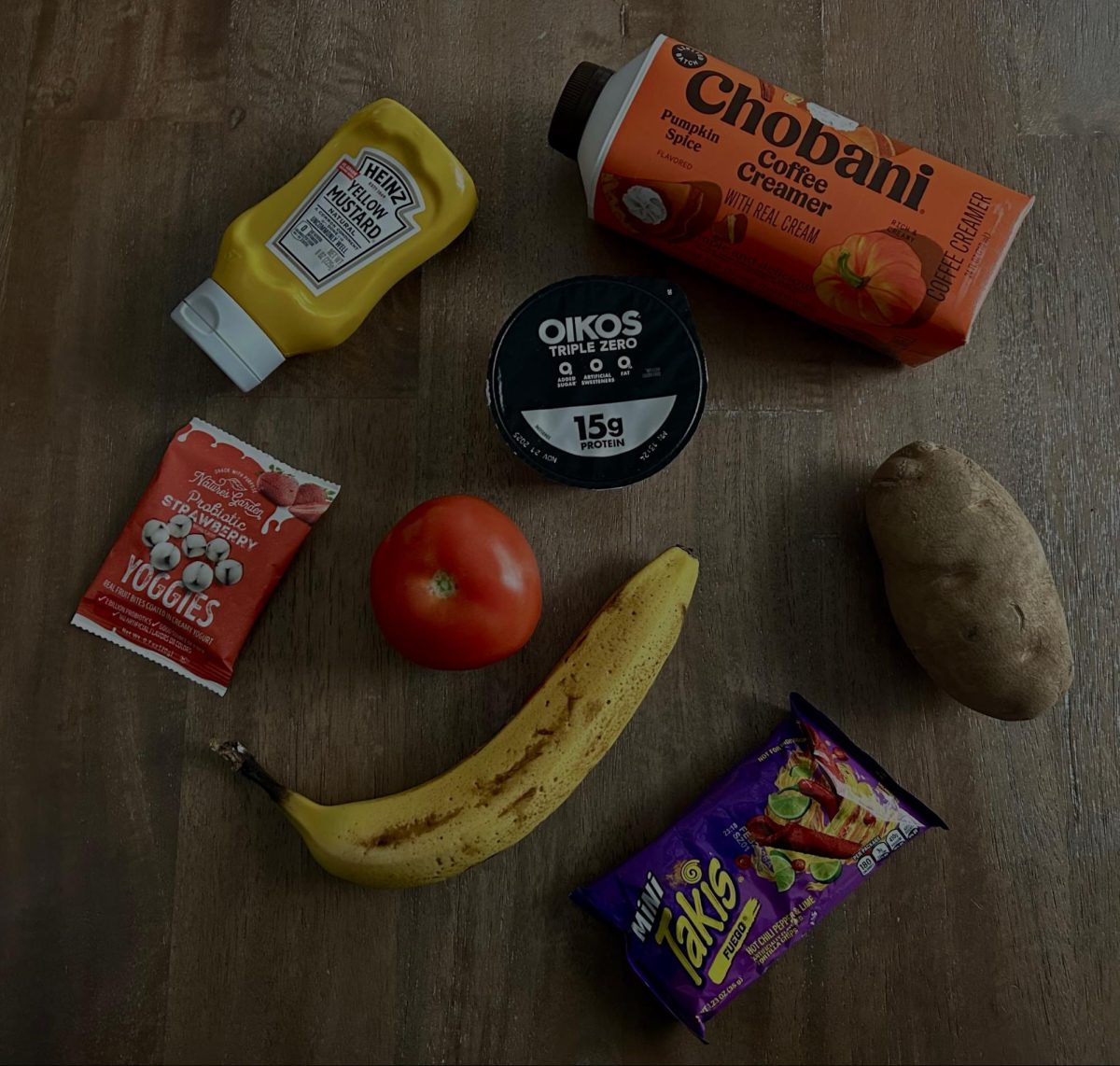

According to the National Library of Health, there are at least 950 substances in American foods that are not permitted in Europe. Chemicals linked to numerous health problems show up in hundreds of products that line the shelves of the supermarkets. Most common snacks like candy contain high fructose corn syrup, and a lot of baked goods contain potassium bromate, both of which have been shown to be harmful to people’s well-being.

“I feel really gross after eating chips,” junior Josephine Boucher said. “It just makes me feel bad and bloated.”

Boucher does not feel this way for no reason. Most processed foods have high levels of salt, which retains a lot of water, and ingredients like refined sugars and carbohydrates, which the body can not digest easily. In fact, a study performed by the National Library of Medicine also describes an obvious association between high intake of these types of ingredients and increased risk of developing diabetes, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration and obesity. The effects go beyond bloating.

“Most of the ingredients in food today cause sickness and cancer,” health teacher Keith Snyder said. “It tastes good and it’s addictive, a well-prepared poison.”

If we know these ingredients are a negative for people’s health, why hasn’t anything been done to regulate them?

The main difference between America and Europe when it comes to regulation is the EU requires additives to be proven safe for consumption before putting them on the market, while the FDA uses a “safe until proven otherwise” system, where cautionary actions are taken after these additives are proven to be unsafe for consumption. The reason a lot of the proven harmful substances that plague grocery stores haven’t been regulated is because of the “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) loophole, which allows food manufacturers to simply say that the ingredients they use are safe without prior approval.

According to the Center for Science in the Public Interest, the FDA also allows these companies to hide some of these preservatives behind unassuming names like “artificial flavors,” “natural flavors” and “spices” instead of specifying each individual substance by name.

In addition to these loopholes, federal budget cuts have weakened the FDA’s oversight over a lot of the food industry. A lot of staff was fired, which has limited safety inspections. With fewer resources dedicated to research, companies face less accountability, letting more of these dangerous preservatives slip through the cracks unnoticed. These cuts also allow major corporations to prioritize profit over quality, resulting in cheaper ingredients, excessive additives and heavily processed products that sacrifice nutrition for shelf life.

“Companies are always trying to make money,” Jennifer Eubanks, a mother of a current Kaneland sophomore said. “When money is the only goal, they don’t seem to care about anything else.”

As food manufacturers cut corners on production, the products became less about nourishment and more about what they taste like, not taking into account their dietary quality.

Despite all the health concerns, many American families view eating these ingredients not as a choice, but a necessity. Processed foods provide convenience and affordability, and with recently rising grocery prices, most households simply can’t afford the organic or clean label alternatives. Another study performed by the National Library of Medicine shows that organic foods are 10% to 40% more expensive than conventionally produced foods, with some prices reaching up to double that percentile. If healthy food is expensive and unhealthy food is cheap, there is a clear issue here.

“I feel as a single mom that was struggling, I wanted to make sure that my child got all the nutrients and everything they wanted or they needed,” Eubanks said. “But now it has just come down to buying whatever is on sale, no matter if it’s healthy or not.”

Eubanks isn’t alone in that feeling.

Last week, I stood in front of the dairy section, holding the same brand of yogurt I’ve bought for years. It used to be $4.29. Now, the tag reads $6.19. The idea of paying 50% more for it wasn’t something I could justify. Every time I return to staples of my diet, the price seems higher.

This kind of financial pressure often forces families to sacrifice quality for quantity. A study by BMC Public Health states that lower income households on average buy less nutritious foods. Like Eubanks, many parents find themselves prioritizing foods that fill stomachs over those that provide nutrition, leading to diets high in sodium, sugar and artificial additives. Over time, this reliance on these products can contribute to health conditions that disproportionately affect low and middle income households as well.

“Processed foods are cheap, they’re easy to prepare and they allow for people’s time schedules,” Snyder said. “With groceries and their rising prices, they still remain one of the most affordable products people buy to feed their families.”

The growing presence of unhealthy, poorly regulated and overpriced foods in American grocery stores begin to show a system that prioritizes profit over health. Families like the Eubankses find themselves needing to choose between feeding their children and keeping them healthy, but that’s the unfortunate reality many Americans share. When healthy food is out of reach, reliance on low quality products becomes unavoidable. Until nutritious food is accessible and affordable for everyone, households will continue to pay the price, not just at the register, but with their well being too.